Teilhard de Chardin and Christ the Omega Point

Teilhard’s Life

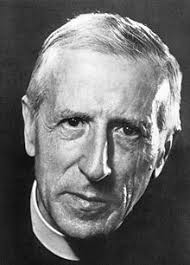

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin was born on 1st May 1881, the fourth of eleven children, in a strict Catholic family in the Auvergne in central France. He became a geologist and palaeologist (student of fossils) and also a Jesuit priest. He spent over 20 years working in China with the French Palaeontological Mission, the Geological Survey of China and the Peking Institute of Geobiology, though the last five years of his life were spent mainly in New York, where he died on Easter Sunday 1955, aged 73. Besides a distinguished scientific career, Teilhard wrote many letters, essays and books throughout his life developing his theological insights that the scientific facts of the formation of the earth and evolution of life on it were not just compatible, but were central, to his Christian faith. Unfortunately, in 1924 his religious superiors took fright at doctrinal errors relating to original sin, as they saw it, in a note he had written. They banned him from then on from teaching, and from publishing anything of a philosophical or theological character without prior approval of a Vatican censor. Consequently he published practically nothing except strictly scientific papers for most of his life. However, with a shrewdness some people find characteristic of the Jesuits, he appointed as his literary executor a laywoman who could not be forced by the Vatican or the Society of Jesus to destroy his manuscripts. And so a large collection of philosophical, theological and devotional writings were published after his death and received with worldwide acclaim. Most of my following comments relate to his best-known book, Le Phénomène humain, or The Phenomenon of Man, written in 1938 to 1940, and first published in 1955.

His language

In developing his ideas, Teilhard uses both scientific terms and words he invents based on them. As a scientist he was very conscious of the processes by which our world was formed. The French word genèse has a wider meaning than its English equivalent ‘genesis’ and can be applied to any form of production involving successive stages oriented towards some goal. He often uses it both on its own and in compounds; for instance, instead of describing a static universe or ‘cosmos’, Teilhard refers to ‘cosmogenesis’, the process by which the universe is gradually becoming what it is finally to be. Geologists call the heavy metallic core of our planet the ‘barysphere’, the rocky layer surrounding it and reaching to the surface of the earth they call the ‘lithosphere’, outside that comes the zone of the waters of the world, the ‘hydrosphere’, and the gaseous layer above that is the ‘atmosphere’. Life scientists refer to the thin envelope on the surface of the earth in which all forms of life are found, intimately connected to each other in a web of relationships, as the ‘biosphere’. To these layers Teilhard added the concept of the ‘noosphere’ (based on the Greek word noos, ‘intelligence’ or ‘thought’, which occurs in English in the slang word ‘nous’ meaning ‘common sense’). As we shall see shortly, by this he meant the global web of thought and conscious reflection generated by human beings.

The Phenomenon of Man

Teilhard claims in his preface to The Phenomenon of Man that the book is purely and simply a scientific treatise[1], observing and identifying patterns in phenomena, and putting forward an experimental law relating recurrences over time. It is not a philosophical or theological essay, and in no way draws on data of Christian revelation. He traces how the universe, the stars and planets, in particular the planet Earth, organic compounds, living cells, higher forms of life, and ultimately human beings, have been formed by increasingly complex combinations of elementary particles. He admits that most scientists of his generation would accept that evolution exists but would deny that it is directed. ‘Asked whether life is going anywhere at the end of its transformations, nine biologists out of ten will today say no, even passionately’[2]. Teilhard is convinced, however, ‘that evolution has a precise orientation and a privileged axis’[3].

He notes that, besides the physical form or organization of material components in a thing (a rock, a bacterium, a plant, an animal, etc), which is the subject matter of the physical sciences and which he calls the ‘without’ of things, there exists a ‘within’, a degree of ‘centredness’ which is imperceptible to science in non-living objects, but which begins to be observable in living plants and animals as a certain spontaneity and a more or less rudimentary consciousness, which then becomes an evident power of reflection and thought in the case of human beings. From his observations he derives a ‘law of consciousness and complexity’, which essentially states that, as the ‘without’ of objects increases in complexity, the ‘within’ also advances towards greater consciousness[4].

This gives him a clear evolutionary path from inorganic molecules to larger organic molecules, the mega-molecules of proteins and viruses, single cells, bacteria, then the multi-layered, many-branched tree of life, the climax of which (in Teilhard’s view) is the class of mammals, and within them the primates, and ultimately human beings. Within this long and gradual development, some steps are of immense significance: evolution crossed a major threshold with the arrival of Homo sapiens and his capacity for reflection and thought. This point in the evolutionary process he called ‘the individual threshold of reflection’. We now have a fairly good understanding of how this capacity developed through the Stone Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age, early civilizations, up to the modern world: the growth of language, communication, communities, social structures, knowledge, religion, literature, science and industry. This is the stuff of what Teilhard calls ‘the noosphere’.

For 30,000 years, human beings have spread out over the surface of the Earth. During this period, socialization, which in Teilhard’s view is the latest stage of evolution, has been concentrated on colonizing undiscovered lands and building communities in them. Within the last couple of centuries, because the Earth has a finite closed surface and virtually every part of it is now populated, the waves of socialization have begun to recoil on themselves and interpenetrate: as people packed together more tightly, they found themselves sharing each other’s thoughts to a greater and greater degree. This process, which he refers to elsewhere as ‘planetisation’[5], and which he described in 1938 when television was in its infancy and before the invention of personal computers, mobile phones, the internet or social networking, we now recognize as ‘globalization’. Projecting this evolutionary trend into the future, as individual centres of consciousness (that is, people) coalesce into one centre of consciousness (the noosphere), he sees evolution converging to a single point some hundreds of thousands or possibly millions of years ahead. He calls this hypothetical completion of the evolutionary process ‘the Omega Point’.

This sharing of our thoughts, values and lives involves submerging our individuality in the collective, but Teilhard denies that we lose freedom, spontaneity and the personal element of our human nature: the universal consciousness we move towards will be ‘hyper-personal’, not impersonal. If we reach this ‘harmonized collectivity of consciousnesses’[6], the human race may thereby pass through a second critical point, a ‘collective threshold of reflection’ comparable to the ‘individual threshold of reflection’ when Homo sapiens first appeared on Earth.

In his discussion of the ‘within’ and the ‘without’ of things, Teilhard distinguishes two types of energy. The energy that is generally understood by science, which links each element with all others of the same order (that is, of the same complexity and centredness), he calls ‘tangential energy’. This is the energy of the ‘without’ of things, the energy related to matter. He associates a different type of energy, which he calls ‘radial energy’ (sometimes known as ‘psychic’ or ‘spiritual’ energy), with the ‘within’ of things. The radial energy of an organism draws it forward in the evolutionary process towards ever greater complexity and centredness. In the immensely complex organisms that are human beings, this radial, psychic or spiritual energy is a powerful and visible force for uniting them in such a way as to complete and fulfil them, to ‘personalize’ them. Teilhard identifies this energy in humans as the power of love. And he sees the factor that can draw mankind on into the unity to which evolution points as the growth of universal love. He argues that the universe is not being pushed along the evolutionary path by something in the initial conditions or big bang, so much as being drawn forward by radial energy (that is, in its fullest form, universal love) towards the Omega Point. Therefore the Omega Point must be personal and loving, not impersonal, and something existing now and throughout the whole process of evolution.

Whilst the natural climax of the evolutionary process is the Omega Point, its achievement is not certain. We, the human race, have the freedom to choose not to continue along the path evolution has mapped out for us. And if we did so choose, ‘the whole of evolution would come to a halt, because we are evolution’[7]. At the time Teilhard was writing, there was great anxiety and even despair among both European intellectuals and the man in the street, the great totalitarian philosophies of fascism and communism were embarking on a war that threatened to extinguish liberty, and there were many objectors to scientific and economic progress. He was fearful that, if we turned our backs on scientific progress, increasing knowledge and communication leading to unity, we would be wasting all the work that has gone into cosmogenesis since the beginning of time. For Teilhard that was unthinkable. He pleads for man to have faith in progress, in unity, and in a supremely attractive and personal centre.[8] Elsewhere he explains this act of faith as achieving ‘an intellectual synthesis’[9].

Nowhere in the Phenomenon of Man does Teilhard relate these arguments to God or Christ, though in a short Epilogue he notes the rise of Christianity in the last 2,000 years as a separate phenomenon, with a clear hint that he sees it as relevant. I have attempted to give a brief outline of this book, but I have not been able to express Teilhard’s detailed exposition of its scientific basis, nor the visionary (some would say, poetic) style of his writing.

Christ

In other books and essays Teilhard spells out his belief that the Omega Point of his evolutionary theory can be identified with the Christ of Christian revelation. He was very aware that Christ’s engagement with mankind did not consist only of his birth, death on the cross, resurrection and continuing work of salvation through us, his mystical body, but included also his second coming (known in classical theology by the Greek word ‘Parousia’). He understood St Paul’s account of the Parousia (for example in First Corinthians chapter 15) to imply that Christ would achieve his consummation, his plenitude or fullness (in Greek, his Pleroma), at the time of his second coming. In 1920 (long before The Phenomenon of Man), Teilhard wrote in A Note on Progress:

‘Christ, as we know, fulfils himself gradually through the ages in the sum of our individual endeavours. Why should we treat this fulfilment as though it possessed none but a metaphorical significance, confining it entirely within the abstract domain of purely supernatural action? Without the process of biological evolution which produced the human brain, there would be no sanctified souls; and similarly, without the evolution of collective thought through which alone the plenitude of human consciousness can be attained on earth, how can there be a consummated Christ? In other words, without the constant striving of every human cell to unite with all the others, would the Parousia be physically possible? I doubt it.’[10]

He therefore saw Christ himself as undergoing a process of development, a ‘christogenesis’ alongside the ‘cosmogenesis’ of the created universe. Both of these processes reach maturity at the Omega Point, which is, therefore, Christ in his fullness.

The Parousia is important for Teilhard because it is the completion of God’s plan of salvation for the human race, and also because of his belief that you can truly understand the character of someone or something only when they are fully developed. So he wrote: ‘Not a single thing in our changing world is really understandable except in so far as it has reached its terminus…. Hence if we want to form a correct idea of the Incarnation, it is not at its beginnings we must situate ourselves (Annunciation, Nativity, even the Passion), but as far as possible at its definitive terminus.’[11]

Nevertheless, throughout his life he was quite clear that the cosmic Christ of the Omega Point is indeed the man, Jesus of Nazareth. He saw the physical entry of the Word of God into the created universe as a necessary step in Christ’s own development via his mystical body on earth to the universal Christ who would draw all men and all things to himself, that is, his ‘christogenesis’. He saw the institution of the Eucharist as an important means for uniting people’s hearts and minds to himself. He recognized Christ’s role as Redeemer, through his death and resurrection, as an essential element also, though Teilhard’s account of original sin and the mechanisms of redemption are controversial and first brought him into conflict with Rome, and remain, perhaps, the least satisfactory part of his theology. It should be clear also that the role of the People of God on earth, that is, the Church and the Christian faith, are essential to the task of the Omega Point in drawing all creation forward to himself through the evolution of universal consciousness and unity in unconditional love. However, I cannot in this short introduction go further into the theological riches of these ideas.

Notes

[1] The Phenomenon of Man (London, Collins, 1959) [hereafter PM], p 29.

[2] PM, p 141.

[3] PM, p 142.

[4] PM, p 61, pp 300-302.

[5] e.g. The Future of Man (London, Fountain Books, 1977) [hereafter FM], pp 129-144.

[6] PM, p 251.

[7] PM, p 233.

[8] PM, p 284.

[9] Christianity and Evolution (New York, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1971), p 98.

[10] FM, p 23.

[11] Panthéisme et Christianisme (1923), p 8, quoted in C F Mooney, Teilhard de Chardin and the Mystery of Christ (London, Collins, 1966), p 72.

Trailer for next session

Next week, in the last of these sessions, we will look at the views of a French theologian who, as far as I know, has never been criticised by the Vatican, although some of his ideas are a little unusual and not necessarily comfortable. He is not well-known in English speaking countries, but, like some other better-known theologians, his understanding of what the Church should be raises, in my opinion, some questions which challenge all Christians and especially Catholics.

Select Bibliography

English Translations of Books by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

(Note: the following are just some of the editions available)

The Phenomenon of Man, tr Bernard Wall, with Introduction by Sir Julian Hexley (London, Collins, 1959) – written in 1938-49, originally published as ‘Le Phénomène humain’, Volume 1 of his collected works in French.

Christianity and Evolution, tr Rene Hague, with Foreword by N M Wildiers (New York, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1971) – a collection of papers and notes from 1920 to 1953, originally published in French as Volume 10 of his collected works under the title ‘Comment je crois’.

The Future of Man, tr Norman Denny (London, Collins, Fountain Books, 1977) – a collection of papers from 1920 to 1952 (but almost all after the completion of Le Phénomène humain), ‘L’Avenir de l’homme’, Volume 5 of his collected works in French.

Le Milieu Divin, tr Bernard Wall, with Foreword by Pierre Leroy SJ (London, Collins, Fontana Books 1964) – a book-length devotional meditation ‘for those who love the world’, seen by some as a Christian spiritual classic. Le Milieu Divin was written in 1926-27 and published as Volume 4 of his collected works in French.

Books about Teilhard de Chardin

Again, there are many. The one I found most useful in analysing his Christology was:

Teilhard de Chardin and the Mystery of Christ, by Christopher F Mooney SJ (London, Collins, 1966).